2021-06-04

Do you apologise for your poor foreign language skills in multilingual encounters? Find out about the hidden social effects of this common monolingual practice.

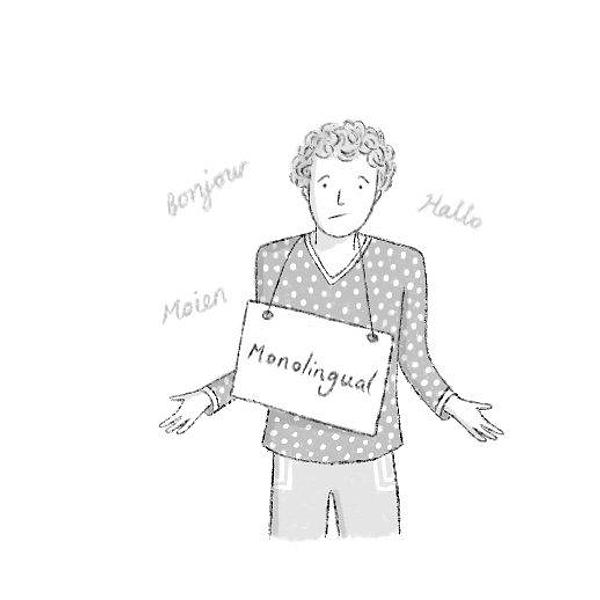

Illustration by Julia de Bres; research summary written by Veronika Lovrits, BM Luxembourg

Investigating the language experiences of migrants in multilingual societies like Luxembourg can shed light on principles of international encounters in global cities. A recent phenomenon of interest is the habit of ‘monolingual cringe’ among English-speaking migrants in Luxembourg.

Luxembourg is a small European Union country with about 630,000 inhabitants. It is a very multilingual place, with Luxembourgish, French, German, and German sign language as official languages. The number of languages spoken in public is even higher due to migration, with people of non-Luxembourgish nationality making up nearly half the population!

English is widely used alongside other languages, so that people who have moved to Luxembourg from English-dominant countries don’t necessarily need to use other languages to get by. But how enjoyable is their position if they speak English only? Researchers at the University of Luxembourg spoke to twelve English-speaking migrants who have settled in Luxembourg to find out about this, analysing interview data and drawings of multilingual experiences. An interesting ambiguity emerged in the results.

Despite the high prestige of the English language and its significant presence in Luxembourg, the participants expressed unease, bitterness or downright distress when talking about using English as opposed to other languages. Their reflections on the privileges they enjoyed due to knowing English were regularly accompanied by shame, embarrassment and expressions of being ‘bad at languages’. If they could not use the local languages, they openly displayed linguistic insecurity, self-deprecation, and regret about living as monolinguals in a multilingual society.

While these reactions may seem surprising among speakers of a highly valued global language, such monolingual cringe has clear functions in talk. A disclaimer of shame or language incompetence can mitigate the unpleasant awareness that English privilege is personally unearned. It helps the migrants save face in situations where they might risk being denounced as lazy or incompetent by their multilingual peers. Pre-emptively adopting a stance of linguistic inferiority can stave off potential reproaches for speaking English only, despite years of living abroad.

Self-deprecating talk about the plight of monolingualism thus allows English-speaking migrants to excuse their lack of performance in local languages. In the end, it keeps use of English socially acceptable in contexts where other languages could be pushed for otherwise. In other words, performing ‘monolingual cringe’ both arises from the social dominance of English worldwide and serves to maintain it.

If you are interested in this topic and want to find out more, Julia de Bres and Veronika Lovrits invite you to read their article: ‘Monolingual cringe and ideologies of English: Anglophone migrants to Luxembourg draw their experiences in a multilingual society’.

You can also check our further research on:

* * *

Further reading